SPRING 2020

use the links below to navigate through my projects

PROJECT 1

Project 1 Reflection

For this project, I worked collaboratively with Rebecca Hennings, Farli Boden, and Mechele Fonck to understand and diagram Montana State University’s public art policy. Our collaboration was successful and enjoyable because we all contributed valuable ideas and hard work to the project. After creating many diagrams, we created an installation in Cheever that affected the space in a manner that both clarified and circumvented the public art policy. We chose to work with the Vitruvian Man painted on the west wall of Cheever’s first year studio because of its optimal location as well as the opportunity it presented to create highly subjective, potentially contentious alterations. Through this exercise, I came to understand the interconnected, rhizomatic nature of campus policies as well as their application, especially within the context of Cheever. Montana State University’s public art policy dictates that all public art on campus must filter through a small committee who determines what art can be displayed on campus. The problem this presents is one of subjective judgment; how can one tiny subset of a large population determine what is appropriate for or desired by the whole community? With our installation in project 1.3, we aimed to shift the power of choice back into the hands of the viewers. We accomplished this by erecting a large, vertical, conveyor-belt-style track of muslin in front of the Vitruvian Man. We provided paints with which people could create whatever they liked on the muslin. The muslin could then be pulled along the track until it aligned with the Vitruvian Man painting behind it. The goal was to create a seamless image comprised of the muslin and the Vitruvian Man when viewed head-on. By this mechanism, people could seemingly alter the appearance of the Vitruvian Man. After leaving our project up for a few days, I realized the importance of having public art filter through a committee. The art that resulted on the muslin was chaotic and distracting. Ultimately, I learned that it is important to consider an entire system when making design decisions since altering a small portion of a system can have drastic effects on many other parts of the system.

Project 1.1 - Virtual Systems and Their Physical Manifestations

The goal of project 1.1 was to discover, analyze, and synthesize the relationships between virtual systems and their physical manifestations. This was a collaborative assignment; I worked with Rebecca Hennings, Mechele Fonck, and Farli Boden. Through this assignment, I came to learn the depth and complexity that every system has. A system never exists simply; by its nature, a system has many internal connections and components as well as multiple connections to other systems. I learned what a rhizome is and how it can be used to look at subjects more holistically and less hierarchically

We began our project by researching different policies that relate to Cheever. We chose to research the public art policy, tobacco consumption policy, air conditioning policy, and lighting policy. We then rhizomatically diagrammed all of these policies and took applicable photos depicting some of the physical manifestations of the virtual policies.

(above) work of Rebecca Hennings

(above) work of Mechele Fonck

(above) work of Farli Boden

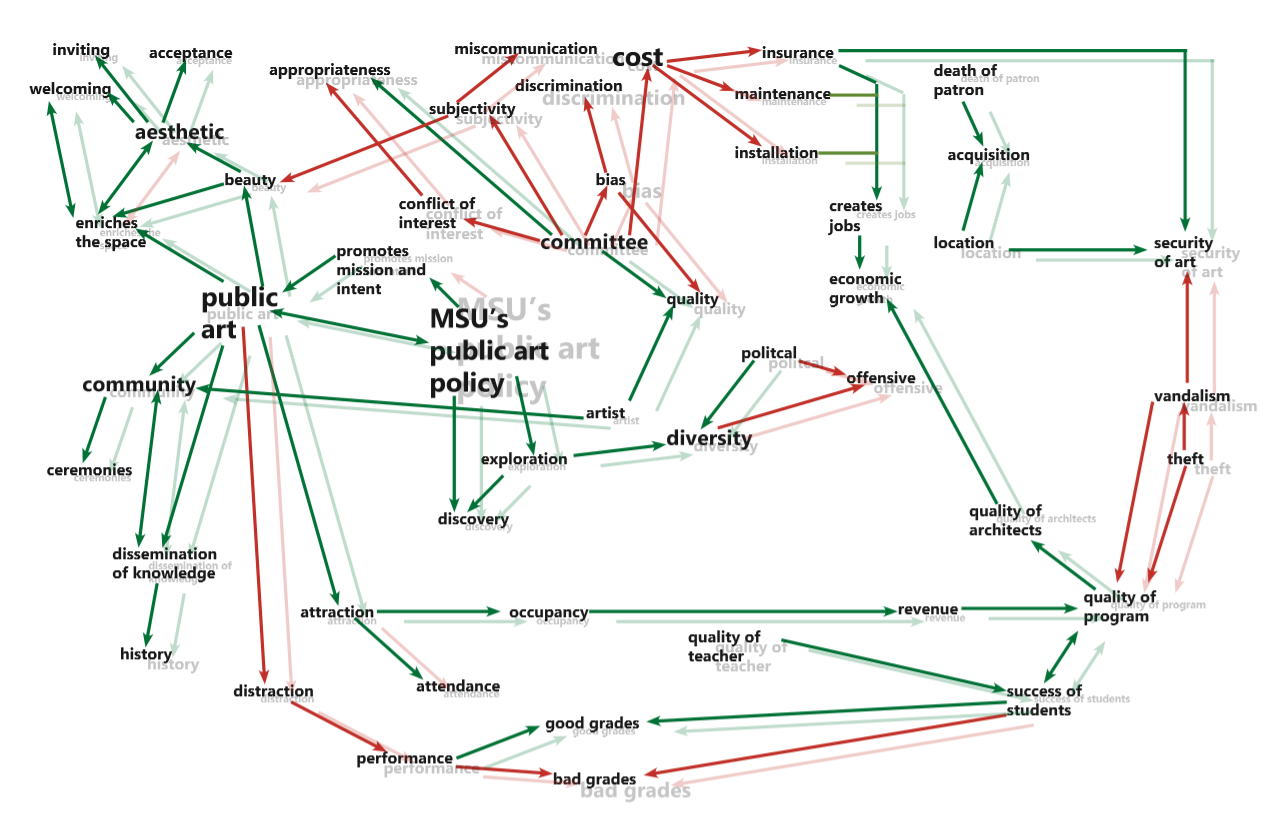

After completing all of these diagrams, we decided to narrow our focus of study to MSU’s public art policy. We continued developing our rhizomatic diagram as we thought more about the quality and strength of relationships between components of the virtual system. In our final diagram (below), the green lines show positive externalities and the red lines show negative externalities. The size of the word relates to the magnitude of that component’s manifestation. The “shadow diagram” shows this policy in a different state than the first; it shows how increasing the strictness of MSU’s public art policy would affect other components of the system. For example, changing MSU’s public art policy in this way would lead to a decrease in the amount of public art being displayed at MSU/in Cheever, which is why “public art” is smaller in the shadow diagram than in the original diagram.

Project 1.2 — Policies, Parametric Relationships, and the Space of Opportunity

Project 1.2 was an individual project. The goal of this project was to create a responsive and dynamic parametric model that physically manifested the virtual relationships of the policy we were studying. Our creation was to expand and clarify the reciprocal relationships discovered in project 1.1. Project 1.2 forced me to think about how to make an inherently intangible set of virtual concepts become tangible. Additionally, I found requirement to make it responsive quite challenging. Through this assignment, I learned how to make strong connections between the tangible and intangible things which I previously thought had little relation. It helped me further understand the active relationships between components within a system.

Iteration 1

For my first iteration, I created a model consisting of a plank, museum board of varying texture, and a sliding museum board panel. The museum board represents public art, and the plank represents MSU’s public art policy. The sliding panel between the two creates an inverse relationship between the two. If MSU’s public art policy is highly enforced, a small amount of quality artwork will be installed on campus (pictured on far left). Conversely, if MSU’s public art policy is not enforced very well, a large amount of questionable quality artwork will be installed on campus (pictured on far right).

Iteration 2

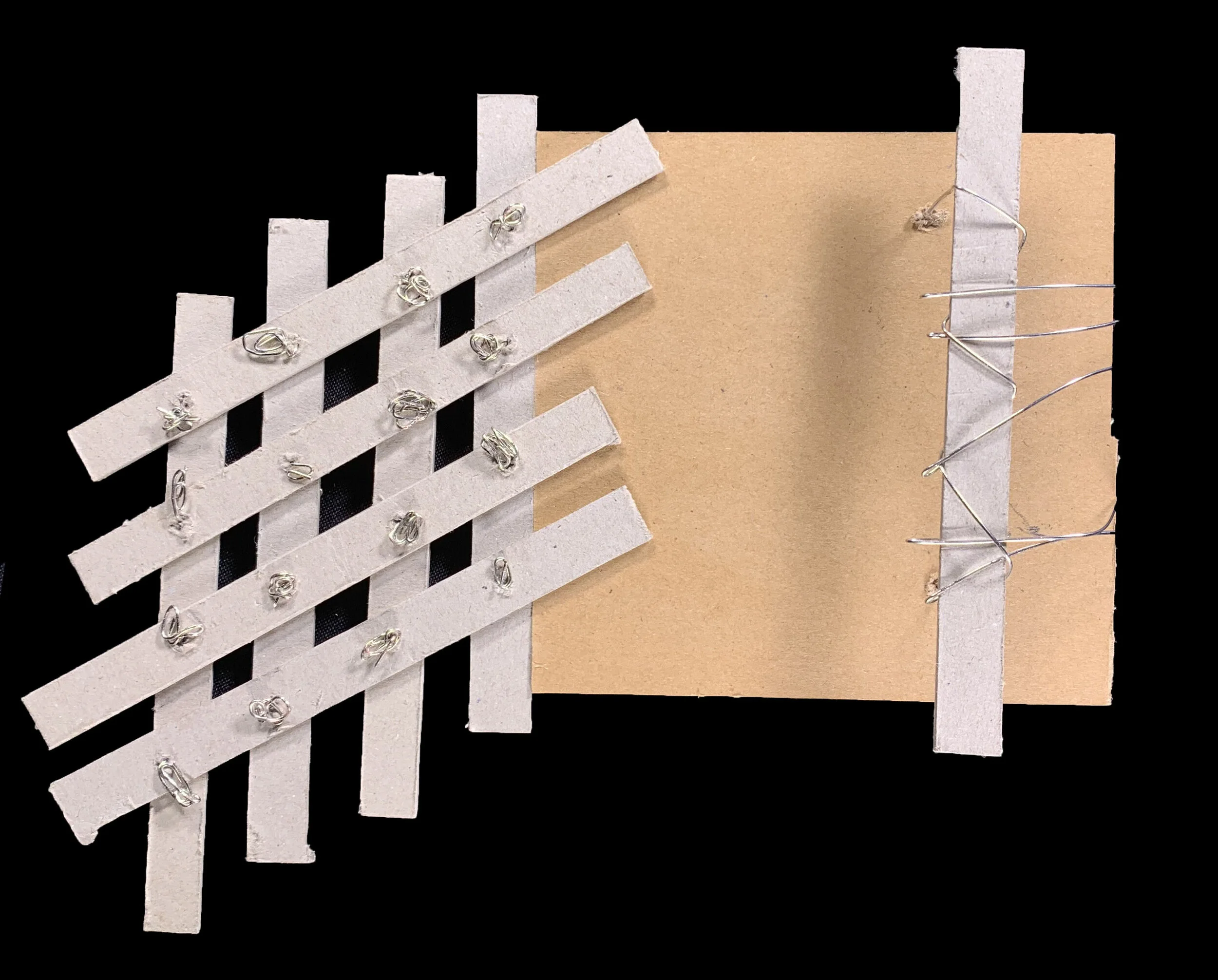

I decided to change tack in my second iteration. I made this model more interactive and responsive than the first. The “web” portion of this model represents components of the public art policy such as beauty, aesthetic, cost, etc. If you push or pull on one strip of the web, it affects all other parts of the web as well. The spaces between the strips of the web represent the channels artists must go through in order to have their work put up publicly at MSU. Art must pass through all the components of the committee in order to reach the public (represented by the museum board/wire “net” at the base.) If the whole system is throw off balance (pictured on the far right,) no art is able to pass through the committee and reach the public.

Iteration 3

My third iteration was very similar to my second. I eliminated the “net” of the public at the base, added an element of color coding for legibility, and attempted to increase the specificity and variability of the model by fine-tuning the joints of the “web” strips.

Final Iteration

For my final iteration, I decided to go in a completely different direction. I abstracted each of the core elements of MSU’s public art policy into three vertical pillars. Other important elements on the policy make up the horizontal elements of the structure. The size of each pillar correlates to the importance of that element. For example, “beauty” is one of the larger horizontal dowels because beauty is a large part of the policy whereas “good grades” is smaller because it is not as directly relevant. Each dowel is free to move within its own socket to move/influence other elements.

Project 1.3 — Spatial Intervention

Project 1.3 was again a collaborative project. I worked with Rebecca Hennings, Farli Boden, and Mechele Fonck. We aimed to create an intervention that mapped and revealed the unexpected aspects of MSU’s public art policy. We created a new physical space that met the rules of the policy but circumvented and expanded its intent in order to critically comment on and question the consequences and the appropriateness of the policy.

Iteration 1

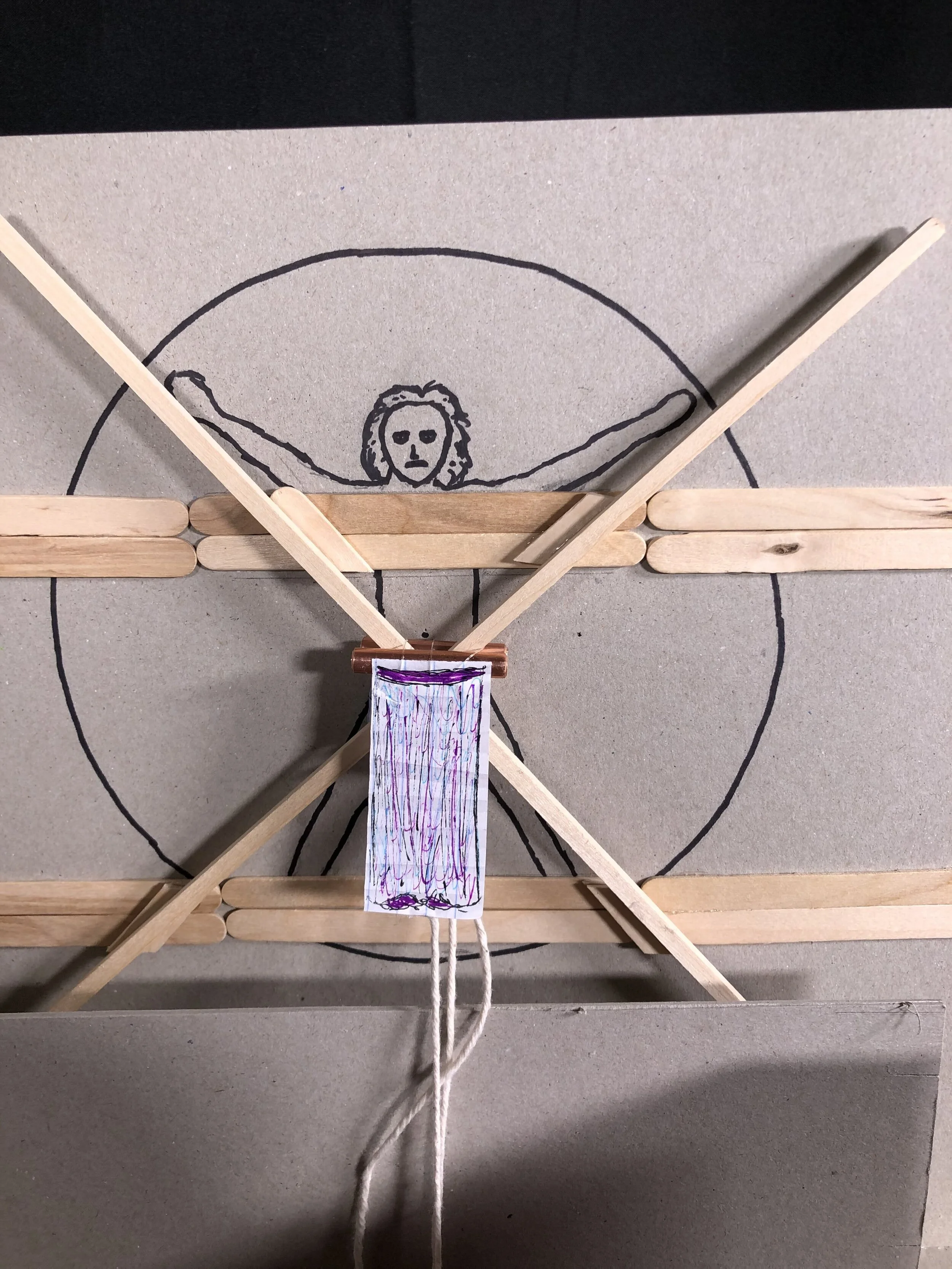

For our area of intervention, we chose to work with the Vitruvian Man painting on the west wall of Cheever’s first year studio. In our first iteration, we thought to erect a series of window-shade-like panels that we would paint different designs on, and the panels would be perfectly aligned in front of the painting in order to effectively change the appearance of the Vitruvian Man. People would be allowed to pull down whichever shade they wished in order to change his appearance to suit their liking. By doing so, we were able to display a new form of art that circumvented the policy’s new art requirements.

Final Iteration

For our final iteration, we decided to make a large loop of cloth that fed through a system of rollers and through a table. We provided paints and brushes on the table so that anyone could paint what they desired, putting the control over public art even more back into the hands of the people. We added a pulley system that allowed the table to be moved up and down for ease of use.

PROJECT 2

Project 2 Midterm Reflection

For project 2, I have been studying the virtual and physical systems present in the Babcock Avenue transect of downtown Bozeman. Specifically, I have been looking in-depth at the portion of Bozeman Creek running through my transect and how different policies and laws relate to the creek and the surrounding area. Through project 2, I have developed a deeper understanding of systemic, holistic thinking and interactions. In my site, I have discovered relationships between policies and their physical manifestations. I have also discovered that there is sometimes a gap between policies and their intended physical effects; intended manifestations do not always come to fruition. Through analyzing policies and physical characteristics of my site, I have discovered that there are also flaws within the system that leave opportunities for exploitation and change. The things I have learned through my explorations in project two will be applicable in all projects I do in the future. I am know much more aware of how many systems are at play in any given area, and how those systems reciprocally affect each other. I have learned that there are spaces of opportunity in system which can be used to affect change.

Project 2.1 — Virtual System Documentation, Systemic Influence on a Transect

For project 2, I decided to study the virtual systems of the transect covering Babcock Avenue in downtown Bozeman. After surveying the site, I decided to delve further into the policies surrounding water usage and pollution in relation to the Bozeman Creek, as well as the zoning and usage of different areas.

Sec. 42.02.030. - Dumping items into channel or polluting creek prohibited.

No person, firm, corporation or association, nor any employee or agent of any person, firm, corporation or association, shall throw, conduct, convey or deposit, or cause to be thrown, conducted, conveyed or deposited into the channel of Bozeman Creek in its course through the corporate limits of the city, or any part thereof, any paper, offal, rubbish, rags, filth, manure, hay, straw, tin cans, hides, dead animals, or anything whatever causing or tending to cause an obstruction or pollution of Bozeman Creek within the corporate limits of the city. (Code 1982, § 9.68.030)

Sec. 40.02.150. - Interfering with or polluting water supply prohibited.

It is unlawful for any person, without the written permission of the director of public service, to manipulate, interfere with and/or obstruct, in whole or in part, directly or indirectly, the free flow of water in any part of the municipal water carrying, treatment and distribution system of the city, whether within or without the corporate limits of the city; and/or to manipulate, interfere with, injure, deface, remove and/or destroy any part of the water carrying, treatment and distribution system of the city, including in whole and in part any and all appliances, pipelines, aqueducts, reservoirs, telephone system and any signaling system or device, gates, headgates, measuring devices, ditches, canals, trenches, drains, valves, valve parts, manholes, hydrants, sprinkling-pipes, fences, gates, posts, signs, notices, storage tanks, Pear Street Booster Station and/or appurtenances of every kind and description of the water carrying, treatment and distribution system and/or used in connection therewith and/or for the protection thereof, and/or any part thereof; and/or to pollute and/or impair the purity and wholesomeness, by any means or manner whatsoever, of any part of the water supply of the municipal water carrying, treatment and distribution system within and without the corporate limits of the city.

(Code 1982, § 13.04.010)

Iteration 1

For my first iteration, I began by studying the specifics of how the policies I was studying were manifesting on both the local and national scale. I researched the specific pollutants that are causing the most damage to Bozeman Creek as well as the greater Missouri River, and color-coded these elements in order to clearly map them geographically. I used varying sizes, colors, and displacements of circles to show the historical changes in pollution over the past 20 years.

Iteration 2

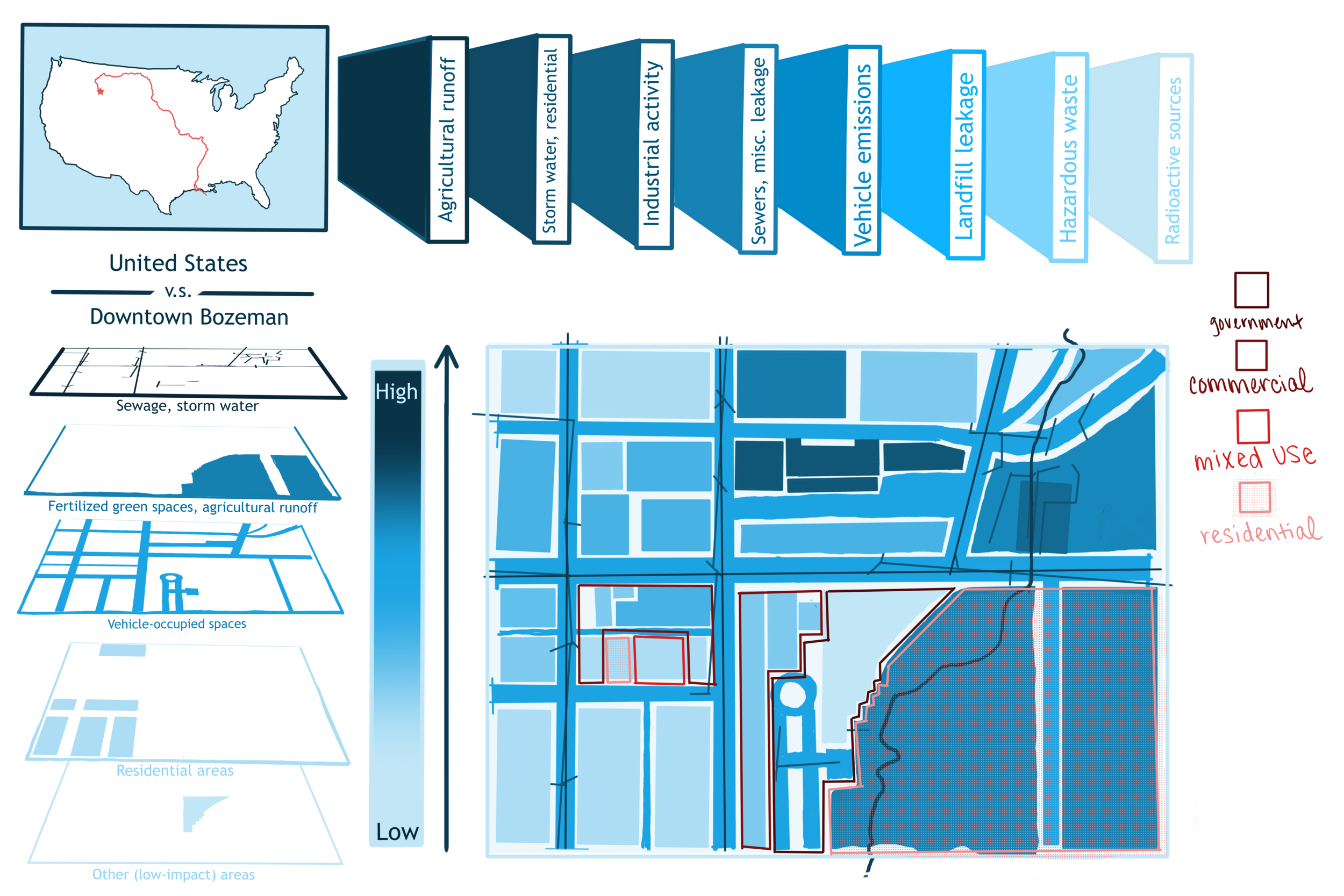

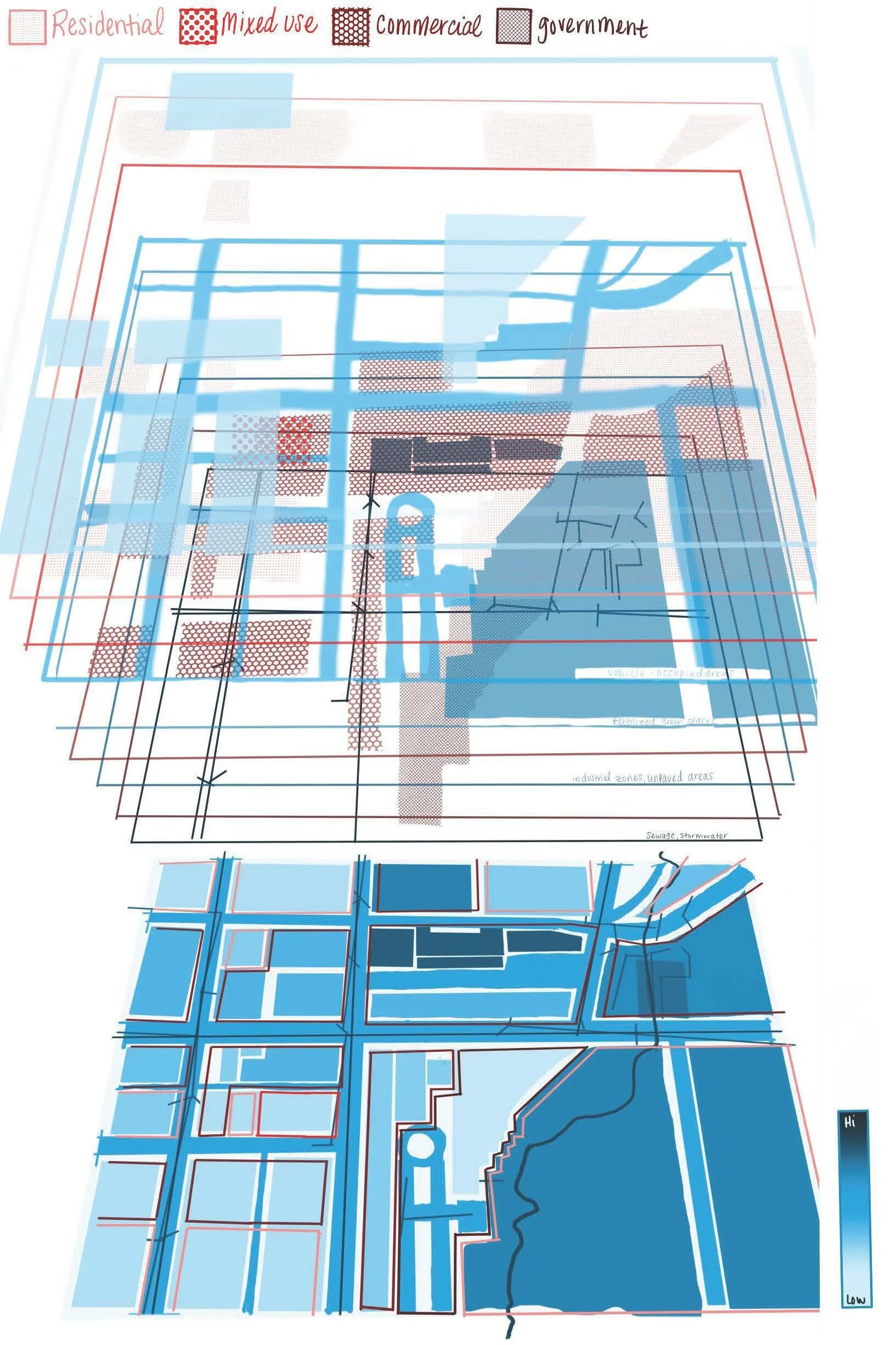

For my second iteration, I decided to simplify the color-coding system I had previously developed in order to make my mapping more legible. I also eliminated the information represented by the circles found in iteration one because I determined it was not relevant or helpful. I expanded the layers of my map to function as a key for my mapping, and I added a layer depicting the different types of land ownership in the area.

Iteration 3

In my third iteration, I chose to eliminate the information about the national scale because I determined it was superfluous, and I wanted to push myself to thoroughly flush out the system analysis and mapping on the local scale. In an attempt to bring more clarity to my mapping, I expanded the “layers-as-a-key” idea from my previous iteration.

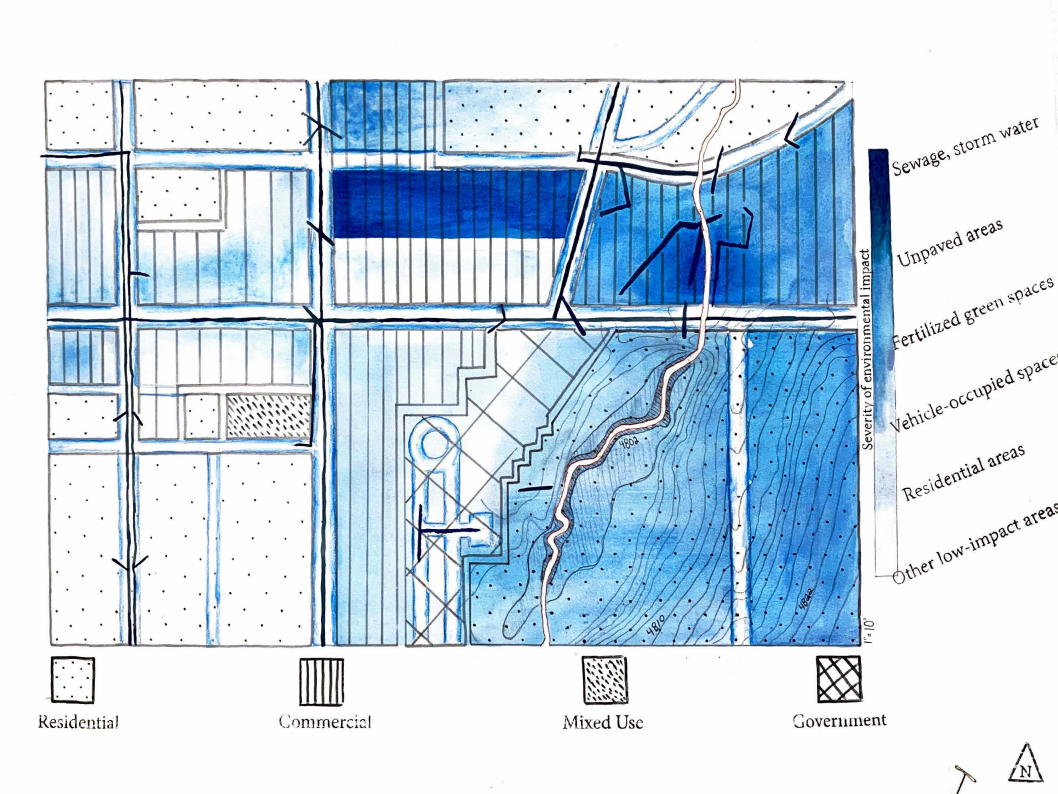

Final Iteration

For my final iteration, I decided to use watercolor and ink on paper to create my mapping. I realized that the geographic mapping of pollutants and their spread inherently exist on a gradient scale. I chose to graphically represent this with a watercolor gradient. The areas of most abrasive pollutants are shaded with the darkest blue, and as the saturation of color fades, so does the impact of the pollutants. The horizontal key shows the variation in line weights I used to achieve mapping the different designations of land types in the area. I added topography surrounding the river to show that the entire area slopes towards the creek.

Project 2.2 — Reciprocal Relationships

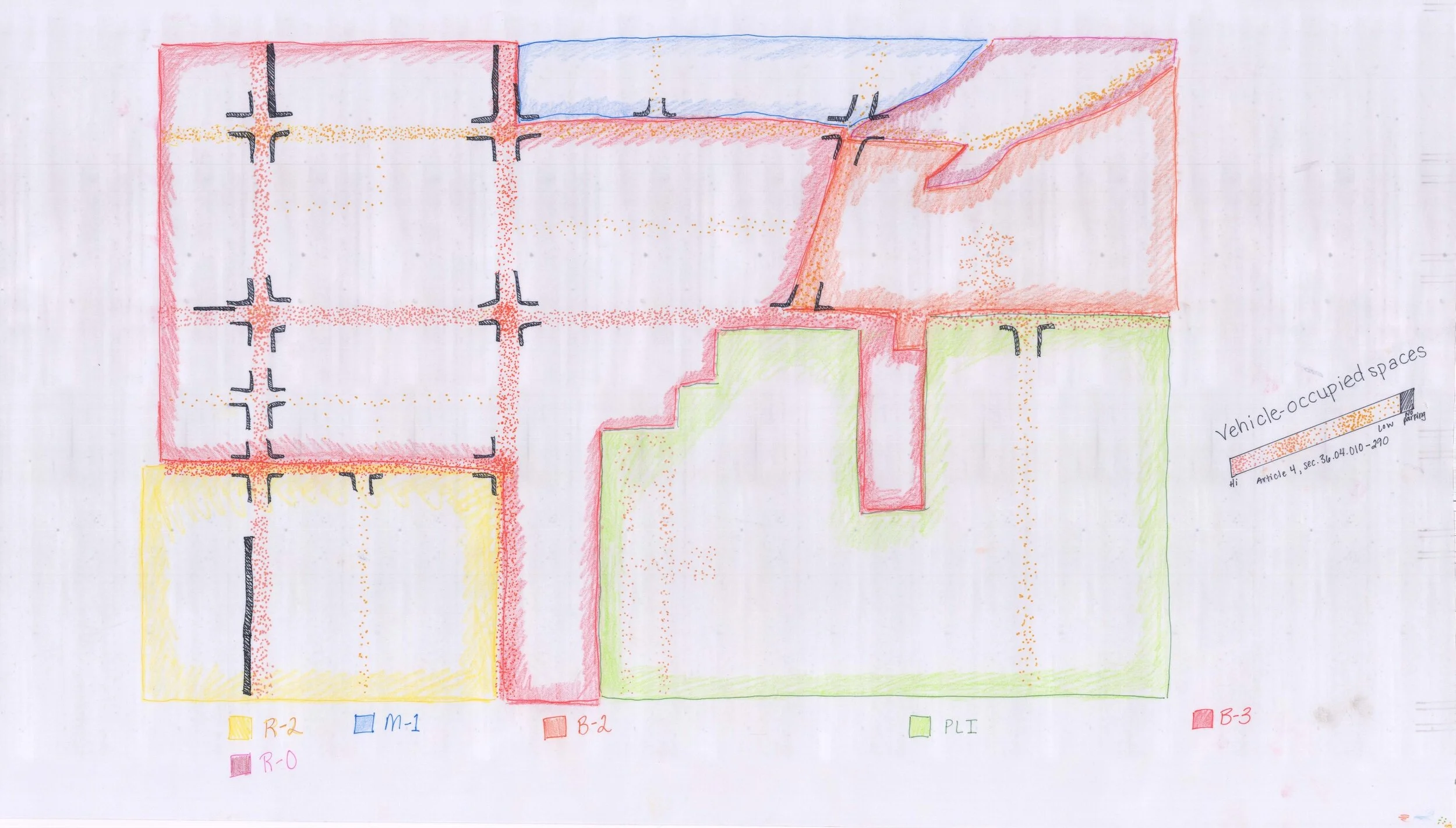

For project 2.2, we were tasked with creating a vellum overlay on our base map created in project 2.1 that delved further into the relationships between virtual policy relating to our transects and the physical manifestations of those policies.

(without mapping)

(with mapping)

My overlay included more layers revealing information about land usage designations, vehicle-occupied spaces, and duration of occupation.

Project 2.3 — Constructing Connections and the Space of Opportunity

For project 2.3, we were to explore the space between our mapping and our overlay relationships by physically constructing the space of opportunity we discovered through the process of mapping and were to evidence the emergence of new realities.

Iteration 1

For my first iteration, I correlated each element I manipulated to one of the virtual elements of my mapping. For example, the height of each element relates to the physical space it occupies on the map. The element’s distance away from the creek correlates to how much that element impacts the creek.

Final Iteration

For my final iteration, I decided to create a more 3-dimensional object rather than objects extruding from one single plane. The size of each wood square face correlates to the physical area that element occupies in my mapping. The density of string from each square frame connecting back to the center dowel correlates to how much that element affects Bozeman creek. The distance of each wood square from the center “river” dowel correlates to how relevant that element is within the context of my mapping, and the colors of the strings relate back to the color-coding system I created in my mapping.

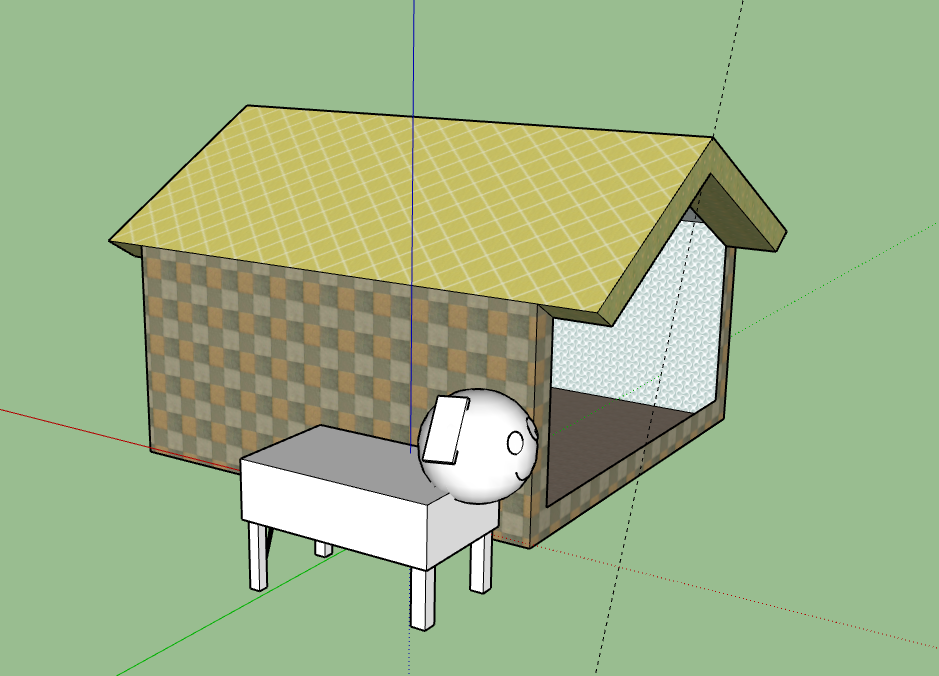

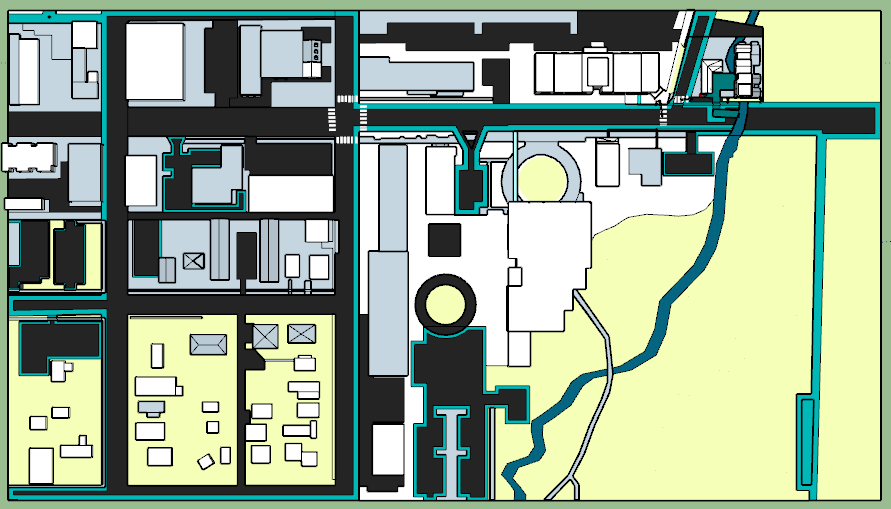

Project 2.4 — Site Model

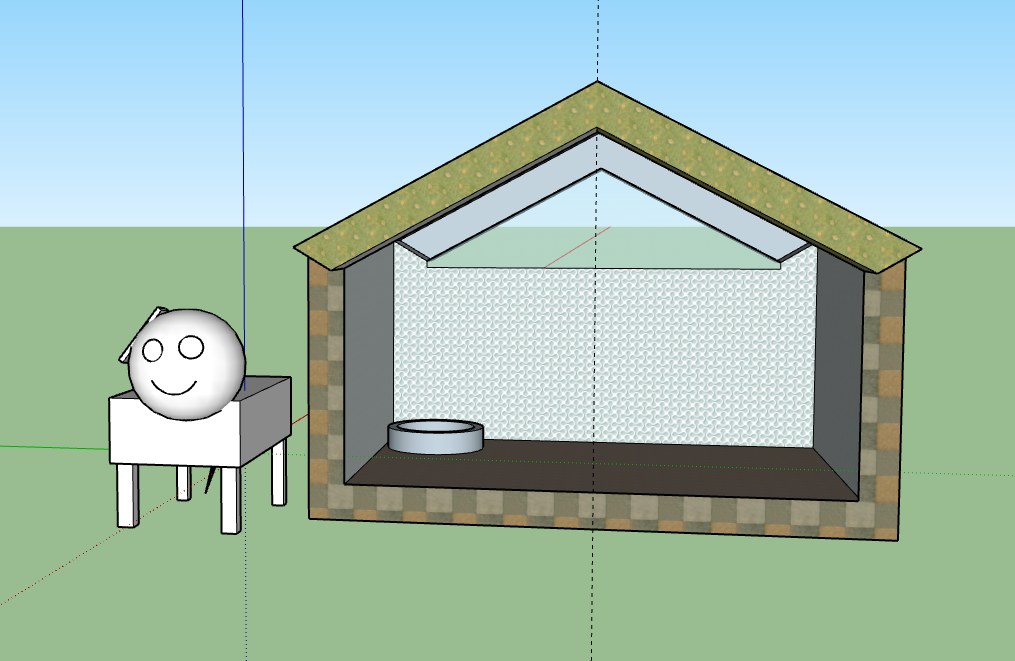

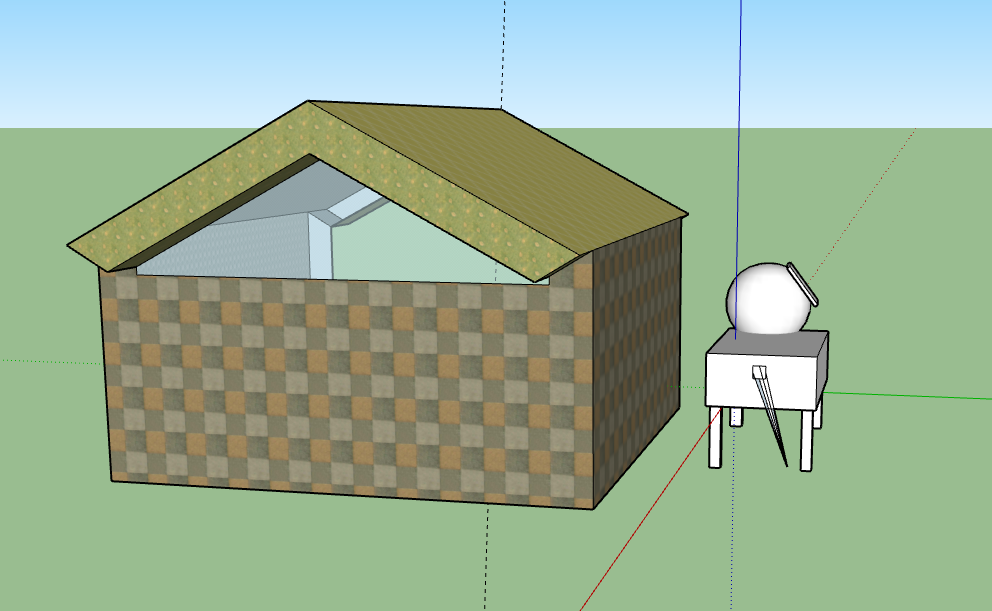

For project 2.4, we were instructed to create a virtual site model in SketchUp based on the investigations we conducted in our previous assignments. Our first assignment was designed to help accustom us to this new medium. I chose to practice modelling a dog and her house.

As this was a completely new medium to me, I tried to push myself to learn how to create different shapes, use a multitude of tools, add detail, and add textures to my work.

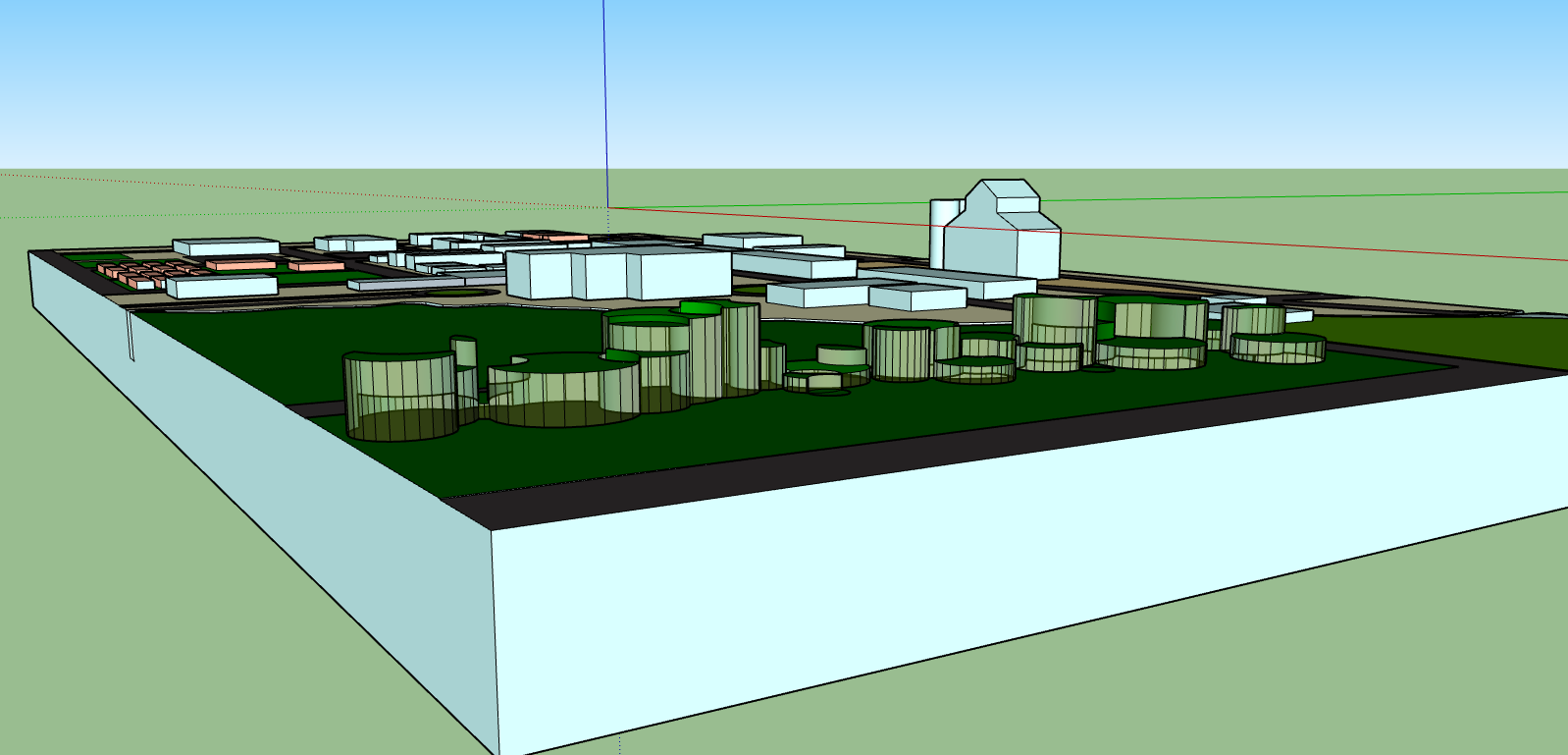

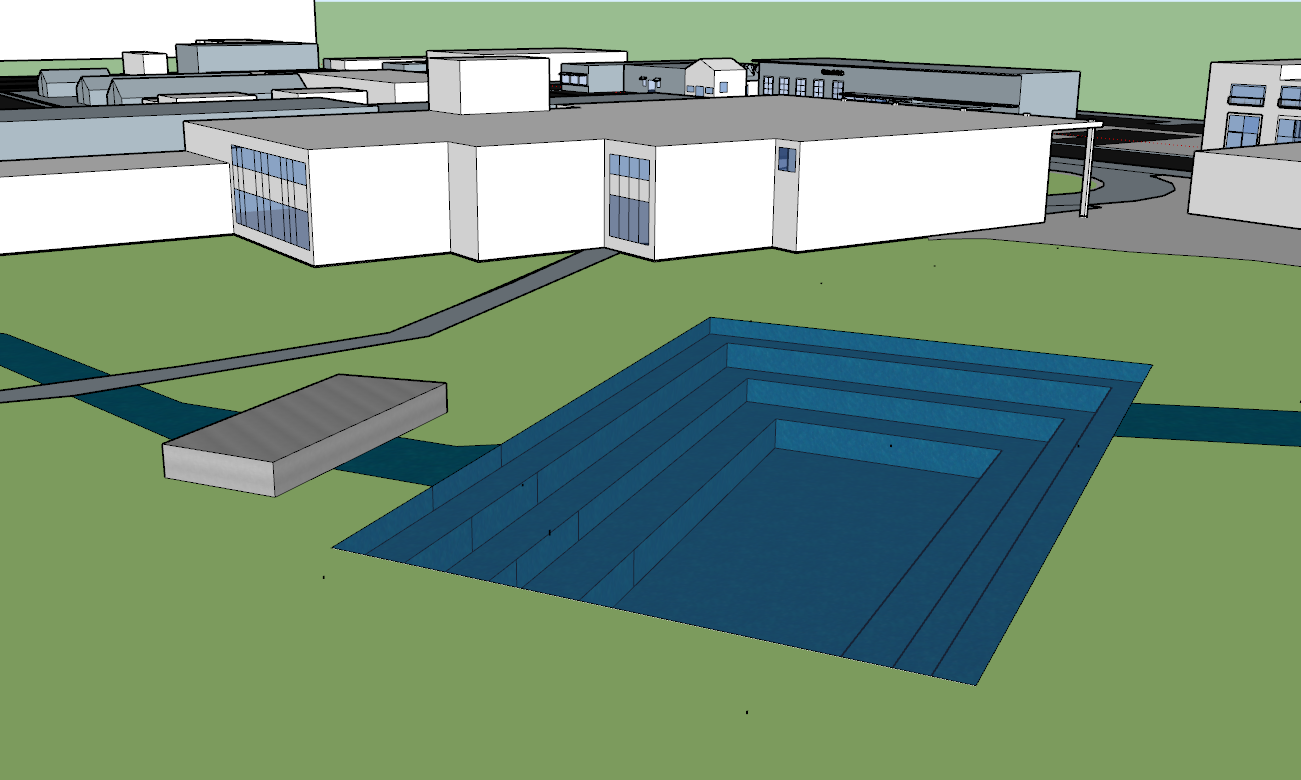

Iteration 1

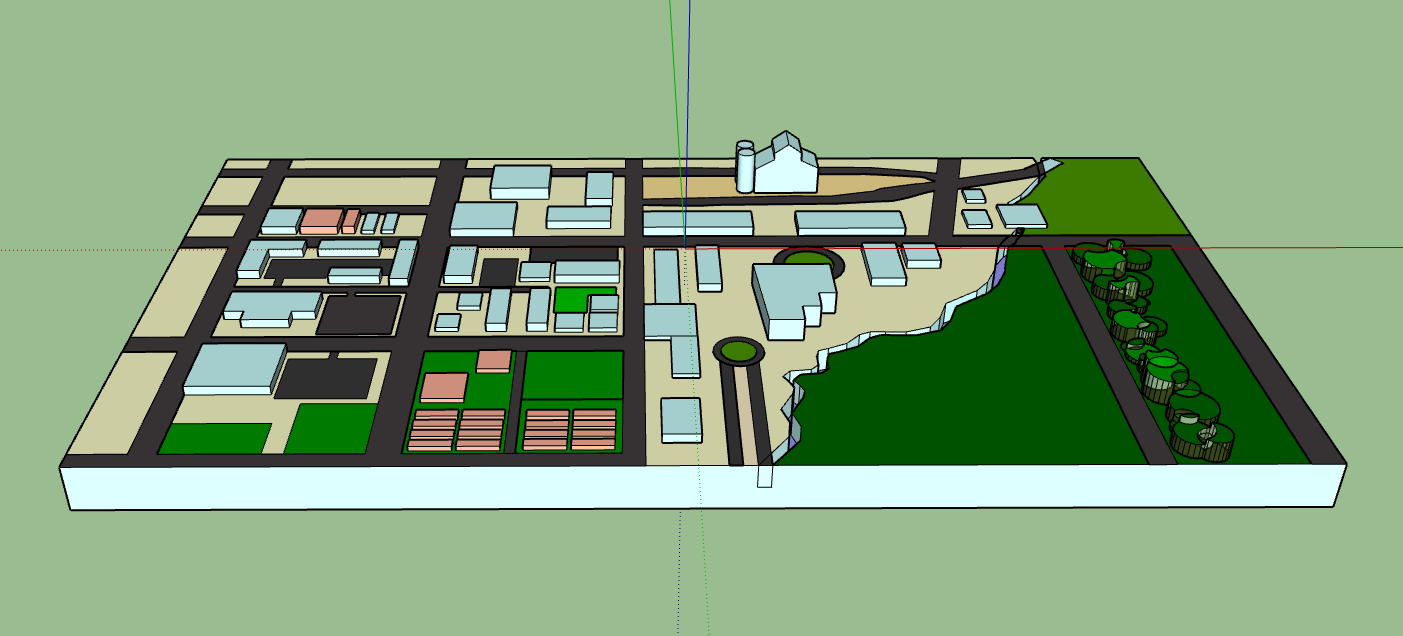

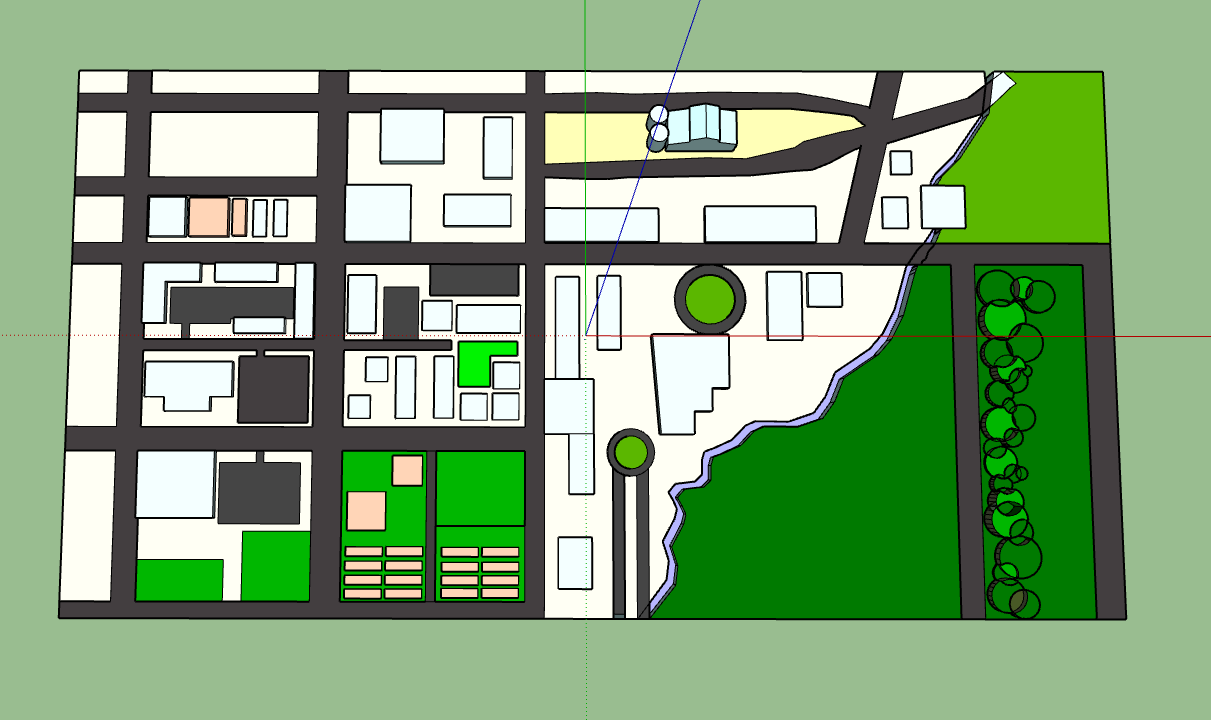

In my first iteration, I chose to model the same area I studied in my map in project 2.1. I color-coded the buildings by type in an attempt to make it easier to differentiate between different buildings, and I chose to model the trees on my site with abstracted shapes rather than specific, accurately located trees.

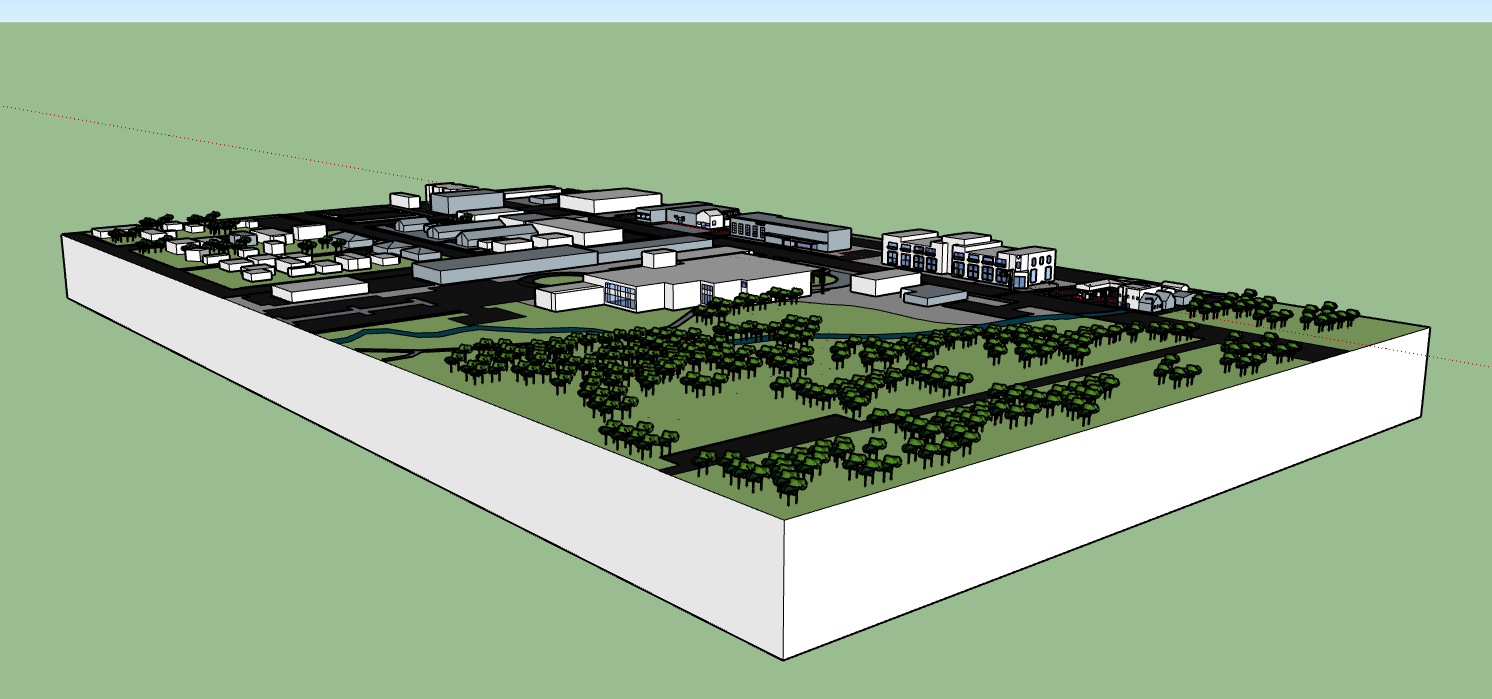

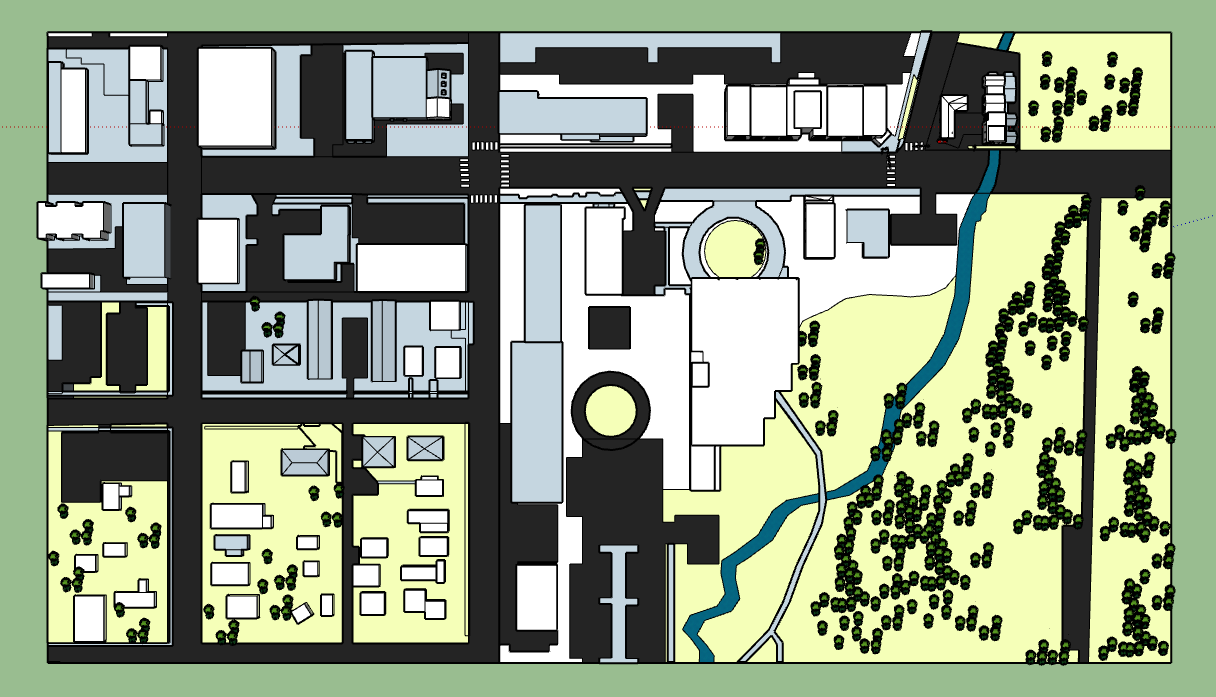

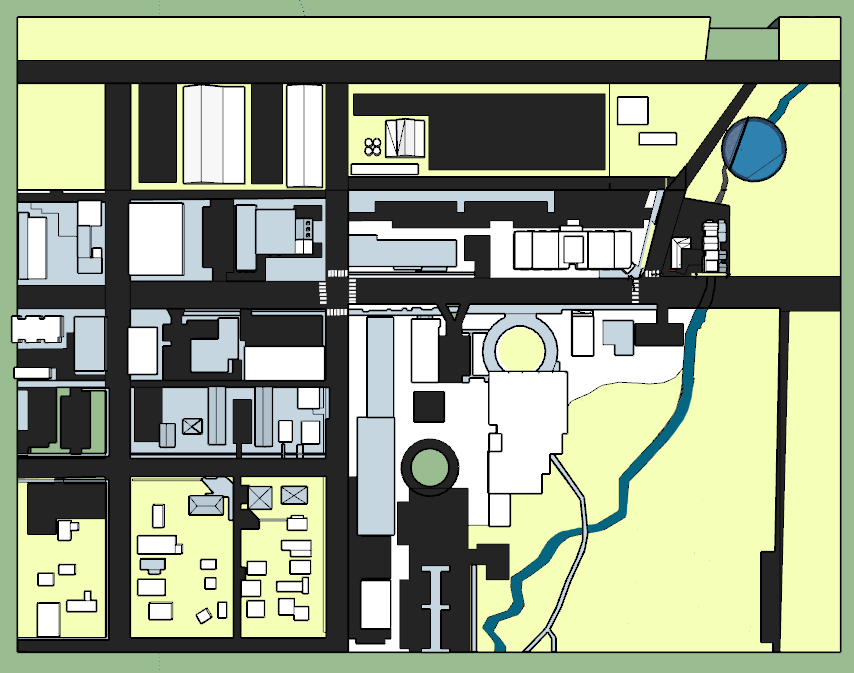

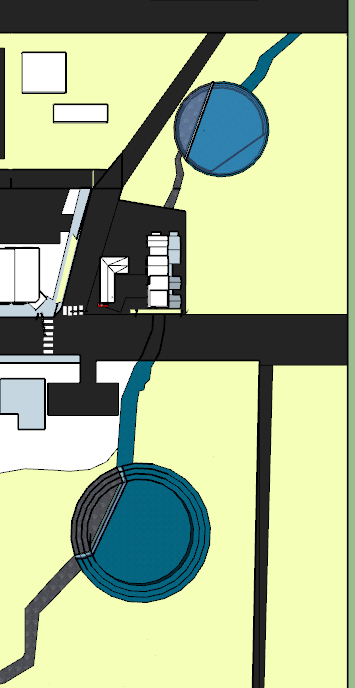

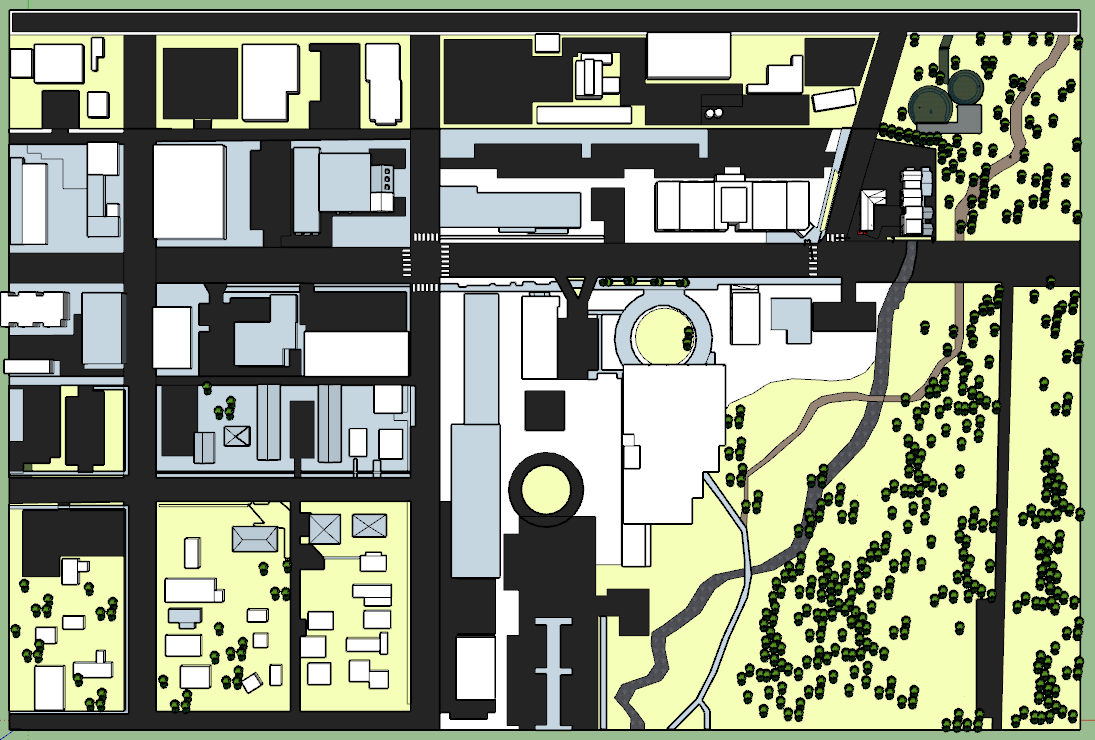

Final Iteration

For my second iteration, I chose to narrow the area I was modelling by cutting out portions of the map that I determined were not entirely relevant to our upcoming project. I also focused on creating more detail across the entire model, especially in the area I determined would be most pertinent to project 2.5. I made my model more accurate than the previous iteration, and worked to create a color scheme that would clarify components of the model and make it easier to navigate.

Project 2.5 — Intervention

In project 2.5, we were tasked with developing a design intervention that leveraged the existing conditions, both virtual and physical, to create a new space that is only possible because of our analysis of the site.

Iteration 1

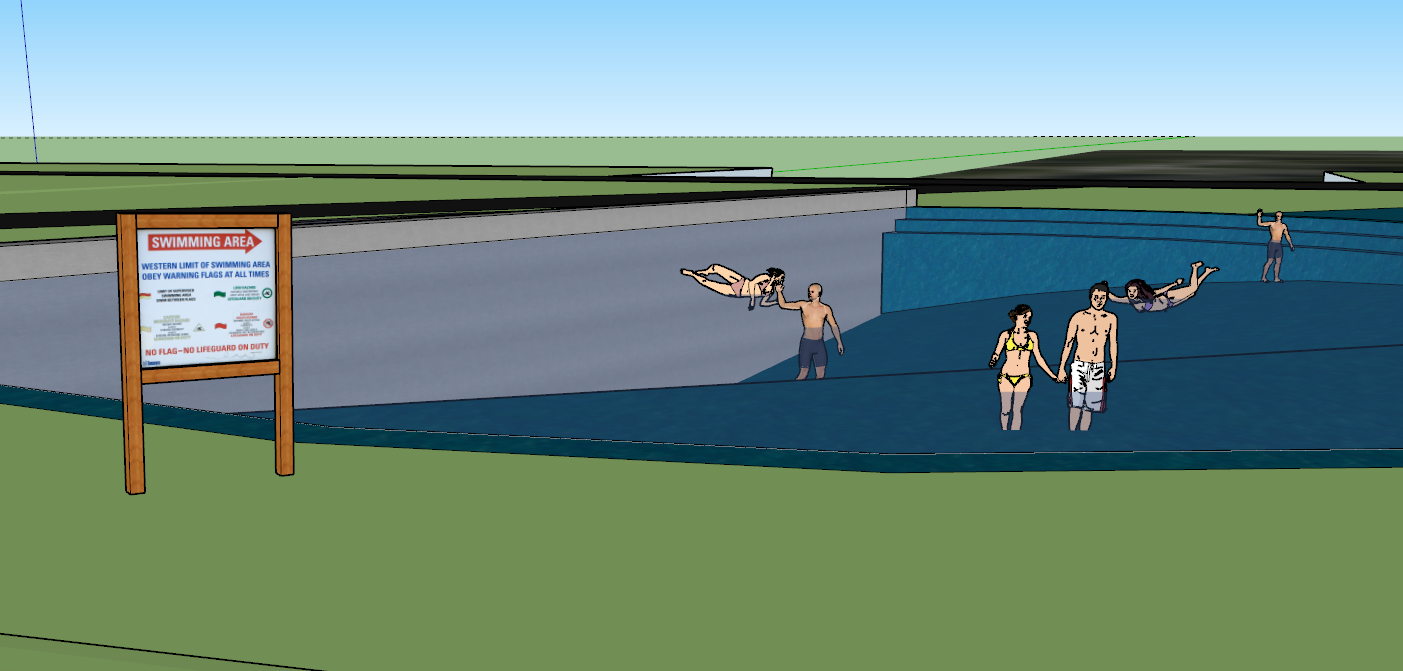

For my first iteration, I experimented with a variety of different ideas. My first idea involved painting the streets with paths of water flow to add physicality to the system of flow on the site. In my next idea, I modeled an intervention in which I created a space that involved exposing the currently-underground Bozeman Creek to bring awareness to its presence. My third idea was to create a sort of pool and filter system that would utilize the creek water to form a recreation space for people to enjoy. It was this idea that I continued to iterate upon going forward.

Iteration 2

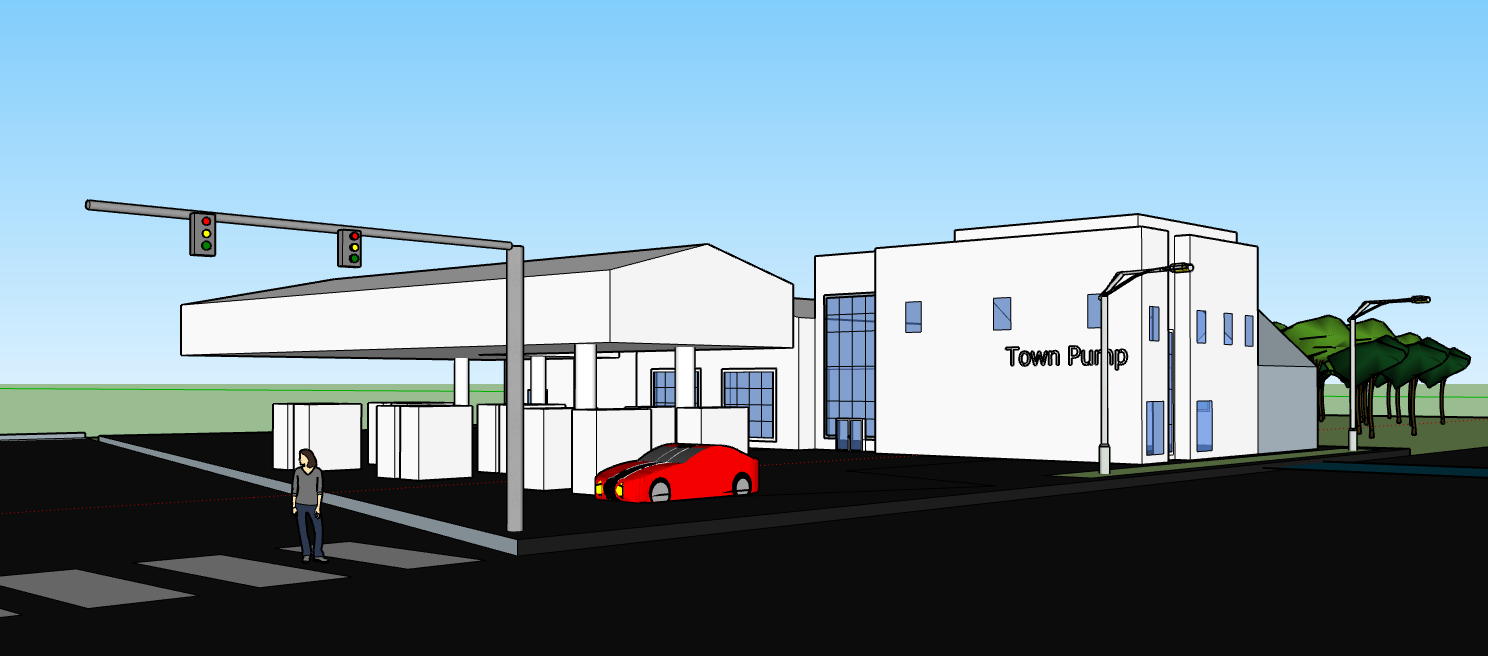

In my next iteration, I changed the placement of my intervention. I realized that my intervention would be more impactful and successful if it were located downstream of one of the greatest contributors of water pollution in this area: the gas station. Bozeman Creek runs directly underneath the Town Pump, and runoff and leakages flow straight into the water. I chose to construct the filter in the pool itself so that people would be forced to acknowledge both the pollution as well as the filtration system present.

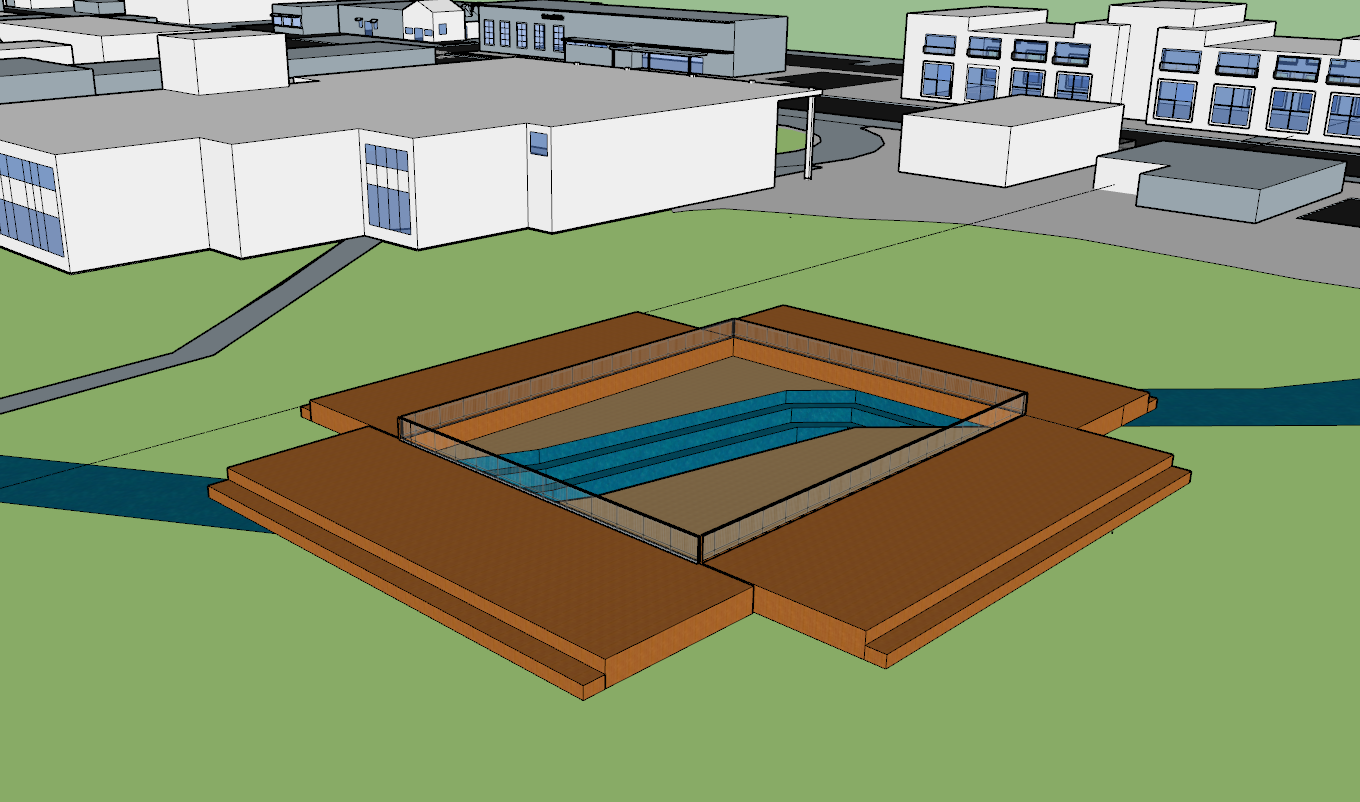

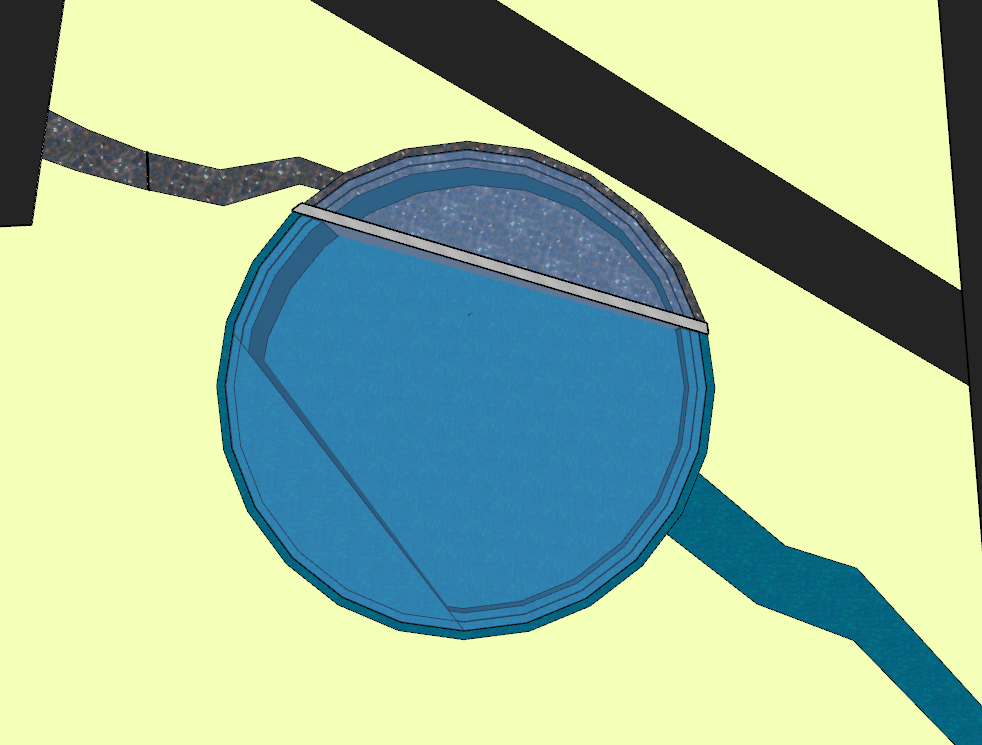

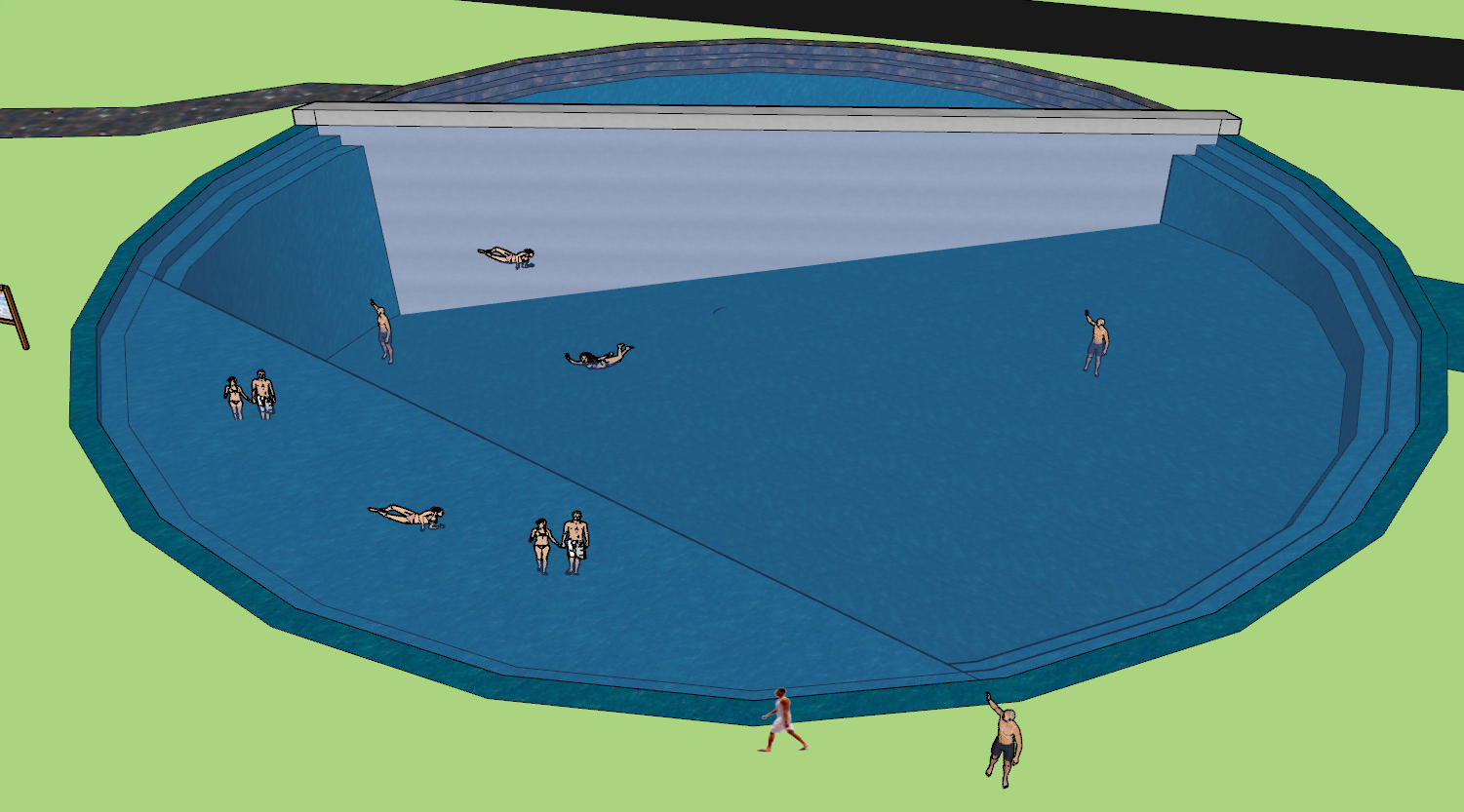

Final Iteration

In my final iteration, I made more intentional choices about my design. I chose to make the pool a circle instead of a rectangle because I wanted the shape to feel more organic; I wanted it to feel more like a part of the systems present and less of an object dropped in this space. I relocated the bulk of the filtration system underground, again in an attempt to make the pool better blend in with the surrounding environment. I added a slope to the bottom of the pool as well as a shallow “shelf” in order to allow access to a wider range of people and abilities.

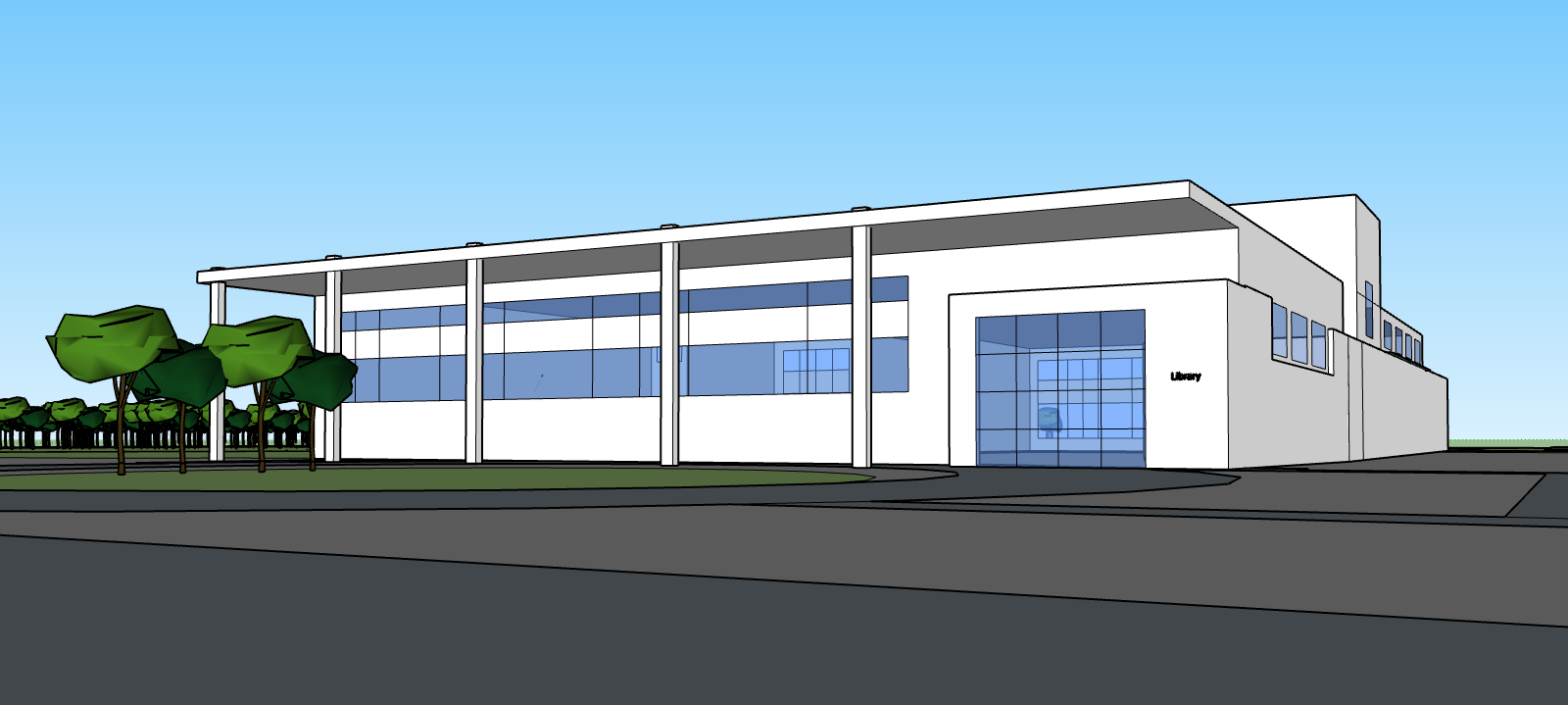

Project 2.6 — Emergent Capacity of Intervention

For this project, we were told to imagine our intervention as it would be ten years from now, knowing that in that time, the intervention became a catalyst for change within the present systems. The goal of project 2.6 was to analyze, re-present, and further the design of our intervention through digital modeling documenting the emergent capacity of the design to have at least ten times the impact.

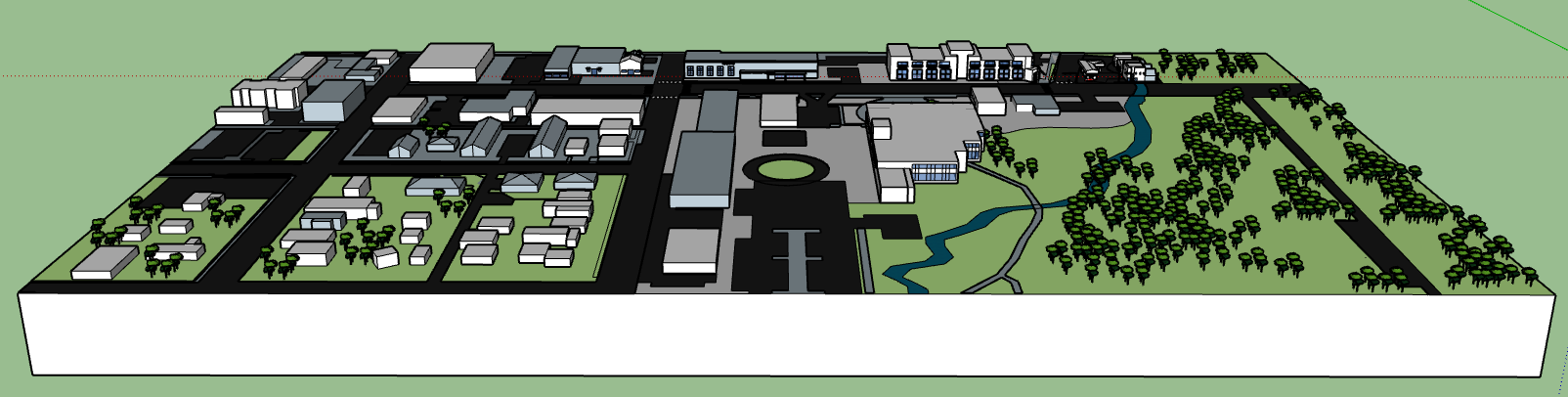

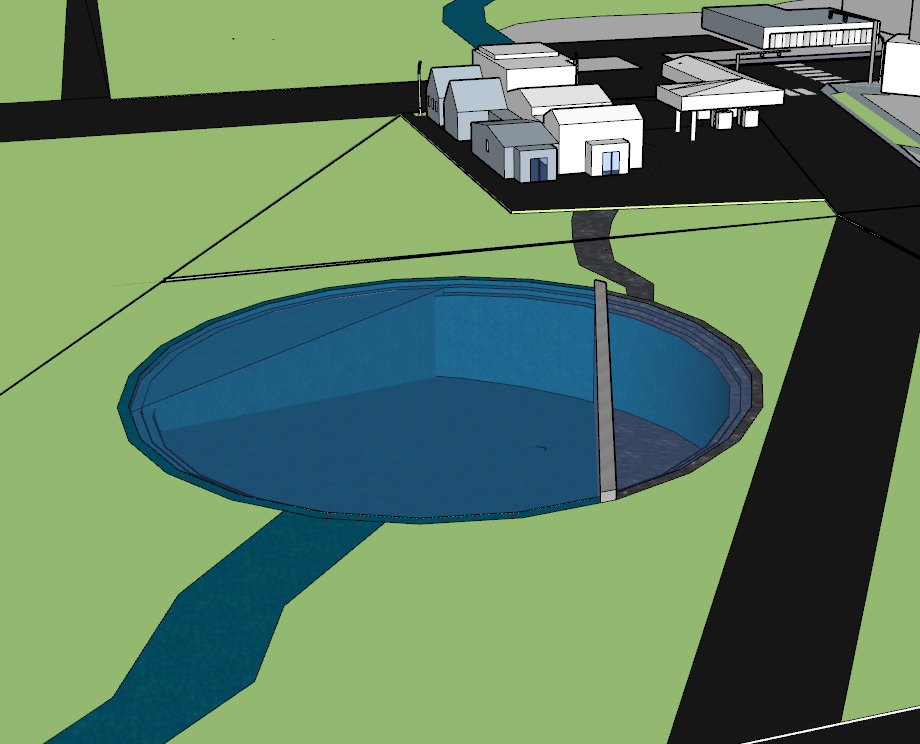

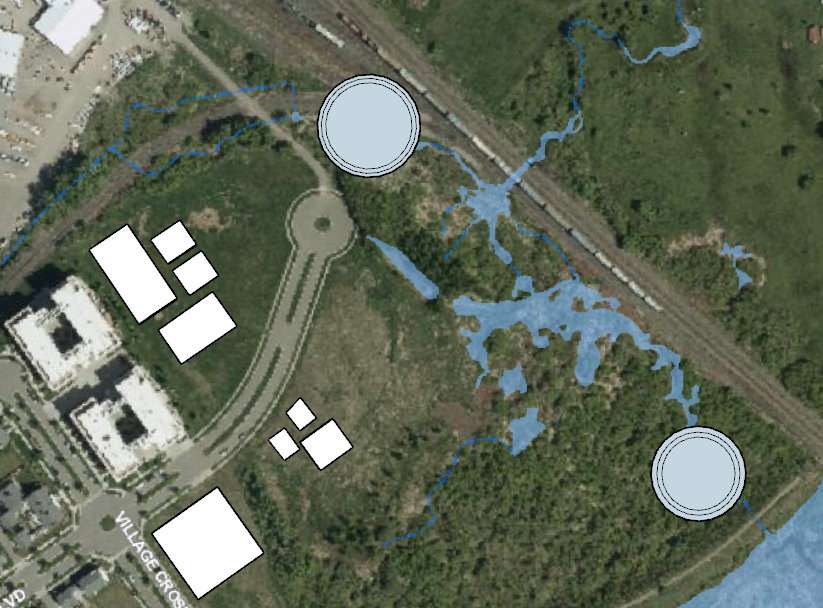

Iteration 1

Bozeman’s population is currently growing very quickly. In ten years, the population will be much greater than now, and thus the need for recreational and green spaces will be greater as well. In my first iteration, I contemplated how population growth would affect my intervention. I created more of the pools I made in project 2.5, adding 2 more pools further downstream by the wetlands which currently are experiencing many issues due to water pollution. I also began modeling population growth by predicting where urban expansion will be the greatest and modeling potential structures based on those predictions.

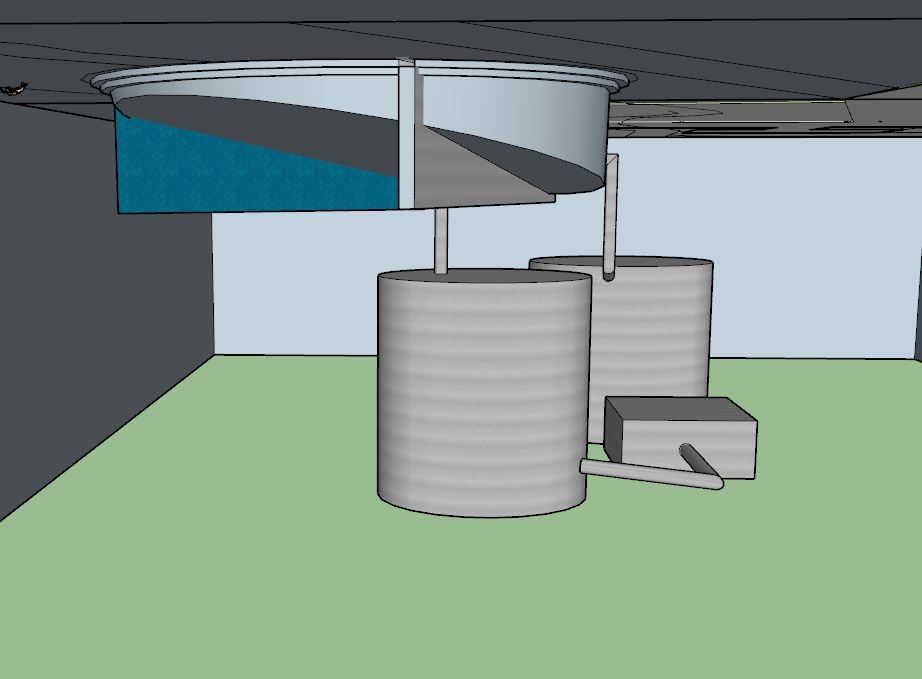

Final Iteration

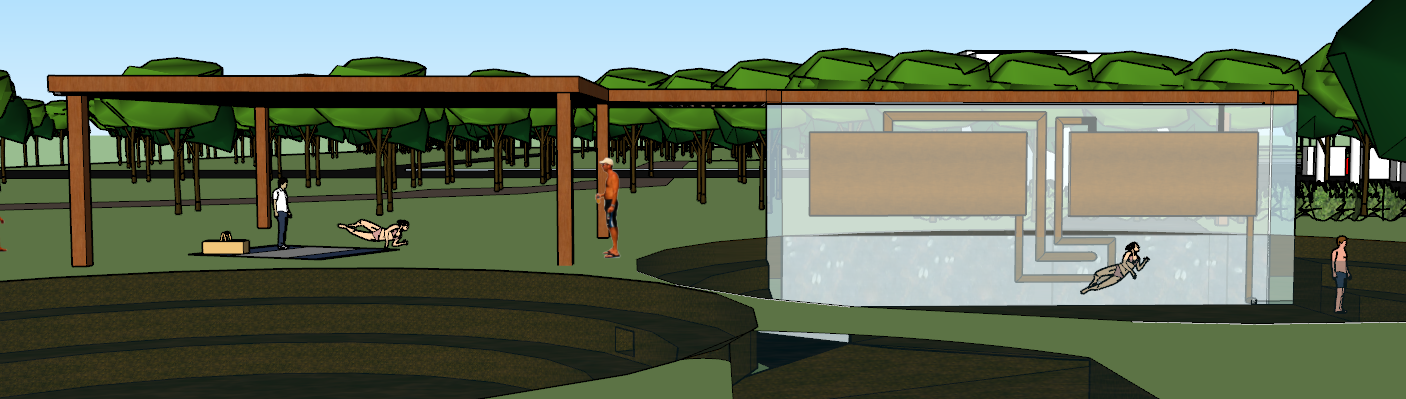

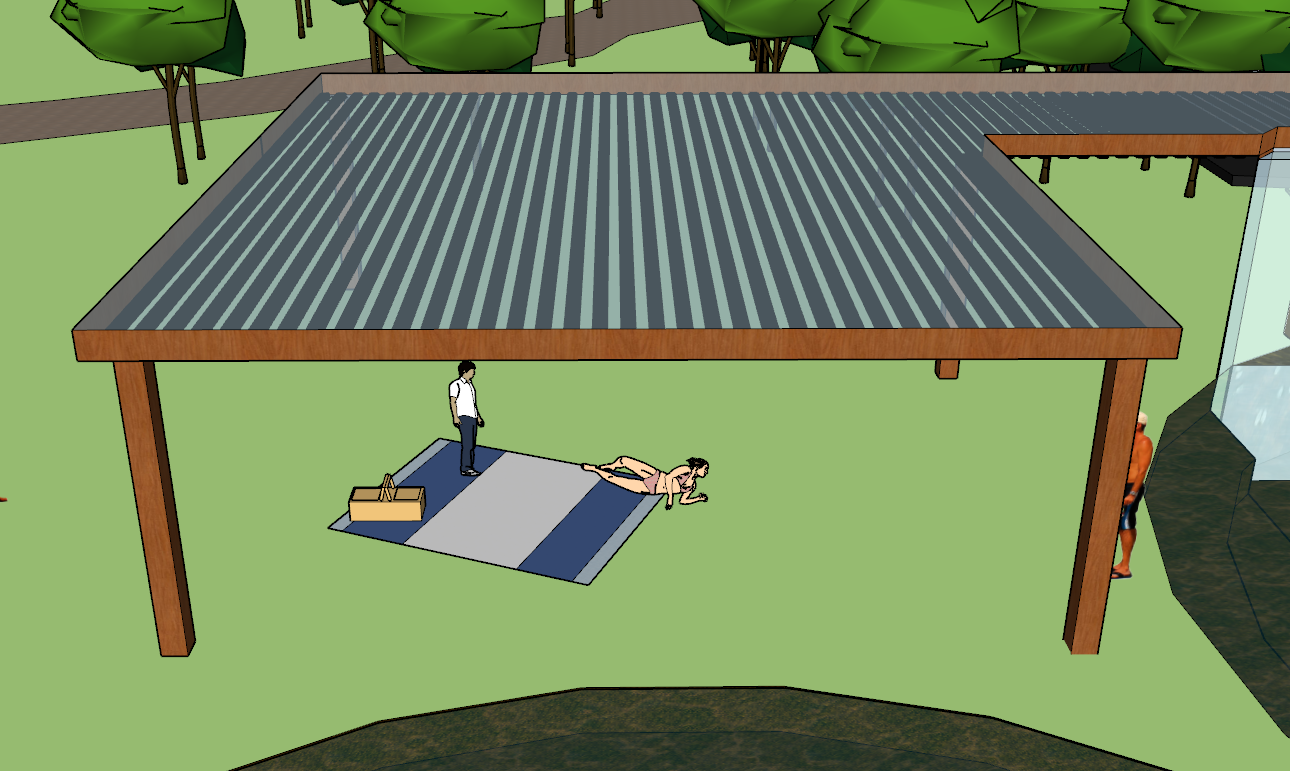

While working on my first iteration, I realized that merely expanding the number of pools did not actually increase the capacity for it to be a catalyst for change. Instead of adding many more pools and expanding my site downstream, I chose to add only one more pool at the original site (picture 4). I did this for a couple reasons. First, I wanted to acknowledge and accommodate the growing population of the city. Second, the additional pool plays an important role in the water processing system. In my new intervention, the creek water flows out from under the gas station and enters the small portion of the pool, separated from the recreation area by the filtration wall (picture 3). The polluted water enters the filtration system, which is suspended in a plexiglas wall. I chose to create the filtration system this way because I wanted to bring attention and awareness to both the pollution and the filtration system. The water is cleaned in the filtration wall, and then is pumped into the black tubes that run through the roof of the structure. The black tubes use solar energy to heat the water, and the heated water is pumped into the first pool. The heated water then flows into the second pool, where the water begins cooling down. Water flows from this pool into shallow geothermal pipes which bring the water temperature back down to its original state. I chose to add this element to this iteration because I realized altering the temperature of the water could potentially be as harmful as the pollutants because it would change the ecosystems downstream. The normal-temperature water would flow through another filters which would remove the pollutants cause by human occupation. The then-clean, normal water would flow back into the creek and continue downstream.

The black tubes in the roof of the structure also serve to create a shaded area below where people can rest (picture 6). Ultimately, the purpose of my whole design was to engage people in the policies I was studying while still providing an area of recreation that did not eliminate green space, which is currently (and will continue to be) threatened by urban expansion. All my design choices aimed to preserve the natural feeling of the space by integrating my man-made filtration structure with the systems already present.